Do as I say, but not as I do

In recent posts, I have pointed out a few of the main reasons why I believe that OFAC name-screening is fraught with so many uncertainties, making compliance unnecessarily difficult for many conscientious financial entities in the U.S. and around the world. I have argued that a subtle, but pervasive set of culturally biased assumptions limit the value of OFAC guidance in the area of name screening.

What are some of the immediate practical effects of these culturally-bound assumptions? Let’s take a look at OFAC in classic information-retrieval (IR) terms to find out.

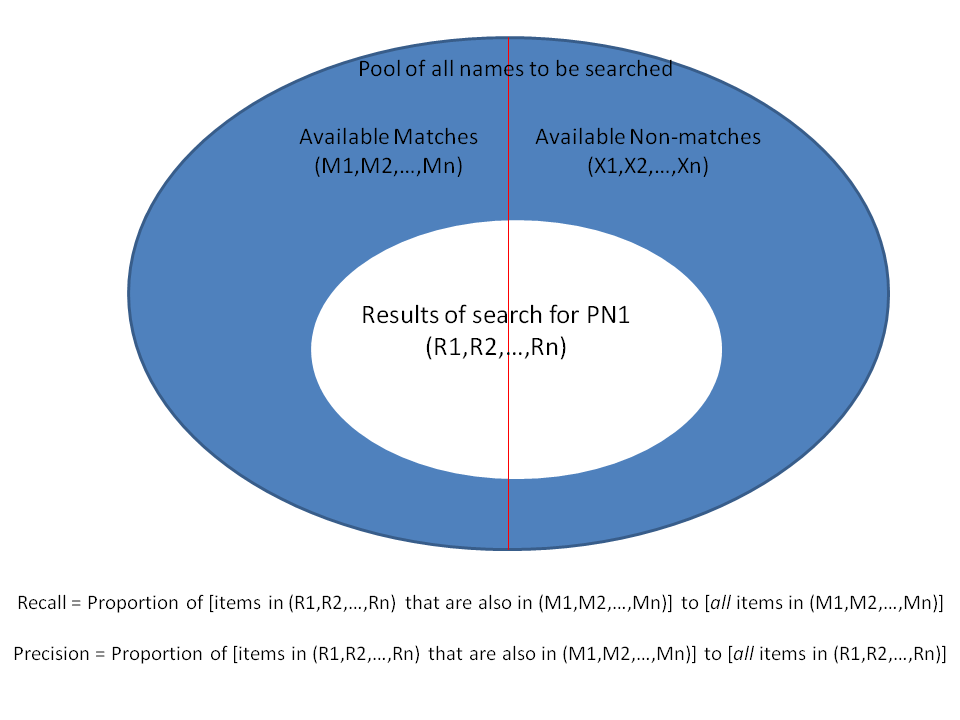

A few key IR terms

For those unfamiliar with IR basics, the effectiveness of any information retrieval system, manual or automated, is typically measured in terms of its precision and recall. In the OFAC name-clearance search, recall will be a measure of the percentage of actual matching names that are returned by a specific search transaction (even if many or all are later disqualified for other, non-name reasons), while precision will be the percentage of names returned by the search that are subsequently deemed to be matches (again, using only the name as a criterion). These two basic measures are elegantly simple in abstraction, yet fiendishly difficult to apply in reality, especially when the pool of names available for searching in a single transaction grows quite large.

What counts as a “good” match in a name-search is largely bounded by the expertise of the person/people doing the evaluation. A native speaker of English might know that a match between the names EDWARD KENNEDY and TED KENNEDY makes sense, but someone unfamiliar with nickname patterns in the Anglo world might decide otherwise. For that reason and several others besides, making accurate, scientific calculations of precision and recall in the world of name-matching is a very contentious and uncertain business.

How “good” is the OFAC search tool?

Nonetheless, let’s try to apply these two concepts to the OFAC SLSA tool, to see how it does when screening the name of an individual who has, say, applied to open a new account at a bank. We’ll represent this person’s name symbolically, as PN1. The OFAC SLSA is used to see if PN1 is a match for any of the names on the aggregated list, and let’s say it produces a non-null set of results, RS={R1,R2,…,Rn}. Then, let’s say we gather a set of 10 top AML/KYC experts to perform the exact same search manually, and these experts, in an astonishing display of unanimity, also produce a non-null set of results when they search for PN1, which we’ll call ES={ES1,ES2,…,ESn}.

The recall of the SLSA search for PN1 (or indeed any search of the OFAC aggregated list) will then be the count of RS members also present in ES, divided by the count of all ES members. The precision of the search will be the count of RS entries also present in ES, divided by the count of all RS entries. Sorry if this is getting a bit tedious, but these two basic IR concepts are at the heart of my issue with the OFAC SLSA and its policy guidance on the name-screening process in an AML/KYC context.

All precision; not much recall

My biggest issue is this: the OFAC SLSA offers practically no help on recall, only on precision. And the advice OFAC offers on improving search precision carries the tacit assumption that all the relevant “hits” needed for a compliant name-clearance are already in the search results. In other words, the OFAC SLSA search results are assumed to already have maximum recall.

If the names that are valid matches are not pulled by the SLSA name-matching mechanism, nothing that OFAC recommends by way of qualifying the results will be of any value. I’m guessing that’s why there are such strong disclaimers concerning the insufficiency of SLSA as a search tool on the OFAC website.

As indeed there should be.

A fish story

Measures of precision and recall are sometimes explained to lay-people in terms of fishing in a lake. Recall measures the percentage of all the fish you were after in the lake that you actually caught, while precision measures how many of the fish you caught were the ones you actually wanted.

Even this folksy explanation of basic IR principles shows a bias towards precision, since every fisherman can tell the fish he wants to keep from the ones he doesn’t, but few (if any) know exactly how many more fish of the kind he wants are still left in the lake after he is done fishing. The tendency to overlook recall in OFAC’s name-screening guidance follows from the same practical constraint: unless you empty the entire lake and examine every fish in it, there is no certain way to tell how many you missed.

So, what is to be done, short of emptying the lake every time a new customer walks in the door? How can you be sure that a given OFAC name-screening process has adequate recall, before you start to throw back the fish you weren’t after?

I’ll stick with my fish story, as a way to address that issue in subsequent posts.